The Essence of Celtic Christianity

It was a pleasure and a privilege for the Primus to be invited to give this talk to seventeen local Norwegian clergy in Etnedal on the 8th of December 2022. The attendees asked many intelligent questions and a memorable time of warm fellowship was enjoyed by all.

God morgen kjære venner. Takk for invitasjonen til å snakke med dere denne morgenen om keltisk spiritualitet.

Even if I can’t speak Norwegian I did want just to begin by greeting you in your own beautiful language. Although Norsk is in a completely different language group to the Celtic languages, yet in cadence and pronunciation it reminds me so much of the Scots Gaelic spoken by some of my ancestors in the Hebrides of Scotland, islands which were actually Norse for many centuries.

This morning I will attempt to cover quite a bit of ground in a short time with this prepared talk, which I will be happy to share with any of you to read later on in digital format. Hopefully we will also have some time for any questions you may have. If you don’t understand something feel free to stop me and ask for clarification.

I expect most of you know a bit about Celtic Christianity but for those who may not I will give you an outline of historic Celtic Christianity from my perspective, and it is fair to say that Celtic Christianity can be viewed from a number of different perspectives. The Roman Catholics, the Reformed, the Anglicans, the Orthodox and various independents like ourselves all come to the subject from slightly different perspectives, yet inspired by the same tradition.

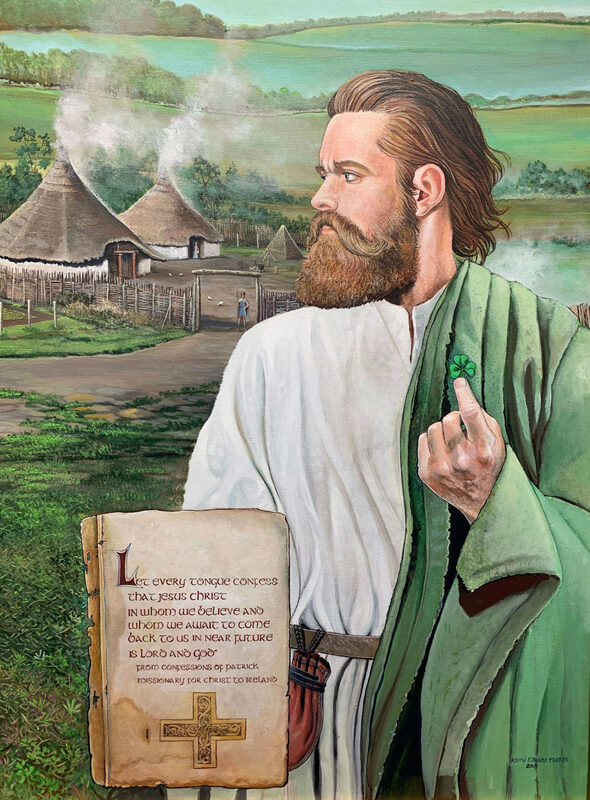

When many people hear the words “Celtic Christian” the image that immediately springs to mind is St Patrick, the 5th century Apostle of Ireland, dressed in green vestments as a Roman Prelate and holding up a shamrock. He was of course an immensely important missionary and as a man of Romano-British heritage the seeds of the Christianity he sowed in Ireland were essentially Roman. In fact, among the sayings of St Patrick that have been preserved, he once said “The Church of the Irish, (which) is indeed that of the Romans, if you would be Christians, then be as the Romans. ...” (Dicta 3). So, from the start, the church in Ireland, and in the other Celtic countries, did not see itself in any way separate from the great Patriarchate of the West based in Rome, though of course in those days the Bishop of Rome was first among equals rather than an infallible source of authority and revelation.

What St Patrick did differently than many other missionaries, was that he did not impose Christianity at the point of a sword or threat of the stake, but rather he affirmed and Christianised all that was good in the native religious traditions of the people, explaining Christianity as the fulfillment of the native Druidic tradition, rather than its antithesis.

Even if I can’t speak Norwegian I did want just to begin by greeting you in your own beautiful language. Although Norsk is in a completely different language group to the Celtic languages, yet in cadence and pronunciation it reminds me so much of the Scots Gaelic spoken by some of my ancestors in the Hebrides of Scotland, islands which were actually Norse for many centuries.

This morning I will attempt to cover quite a bit of ground in a short time with this prepared talk, which I will be happy to share with any of you to read later on in digital format. Hopefully we will also have some time for any questions you may have. If you don’t understand something feel free to stop me and ask for clarification.

I expect most of you know a bit about Celtic Christianity but for those who may not I will give you an outline of historic Celtic Christianity from my perspective, and it is fair to say that Celtic Christianity can be viewed from a number of different perspectives. The Roman Catholics, the Reformed, the Anglicans, the Orthodox and various independents like ourselves all come to the subject from slightly different perspectives, yet inspired by the same tradition.

When many people hear the words “Celtic Christian” the image that immediately springs to mind is St Patrick, the 5th century Apostle of Ireland, dressed in green vestments as a Roman Prelate and holding up a shamrock. He was of course an immensely important missionary and as a man of Romano-British heritage the seeds of the Christianity he sowed in Ireland were essentially Roman. In fact, among the sayings of St Patrick that have been preserved, he once said “The Church of the Irish, (which) is indeed that of the Romans, if you would be Christians, then be as the Romans. ...” (Dicta 3). So, from the start, the church in Ireland, and in the other Celtic countries, did not see itself in any way separate from the great Patriarchate of the West based in Rome, though of course in those days the Bishop of Rome was first among equals rather than an infallible source of authority and revelation.

What St Patrick did differently than many other missionaries, was that he did not impose Christianity at the point of a sword or threat of the stake, but rather he affirmed and Christianised all that was good in the native religious traditions of the people, explaining Christianity as the fulfillment of the native Druidic tradition, rather than its antithesis.

Canon Anthony Duncan, an Anglican writer whom I much admire, explained it thus, “When the Celts became Christian, the ancient myths were said to have been fulfilled in history. Heaven had "married" Earth and Mary, a real woman of flesh and blood, had fulfilled all the mythology of the goddess. She had "named and armed" her Son, who was the real, historical and redemptive sacrifice, validated by his witnessed resurrection from the dead. And the Christian's Good God was experienced by them as a Trinity, like the triple aspects of the ancient Celtic deities. It was a natural progression from the best in paganism, and it was about love, not fear.” This policy of Christianisation of ancient beliefs and practices wherever they were compatible with the new religion, was faithfully followed by later generations of Celtic missionary monks who preached a kinder gospel of love and peace throughout northern Europe and even as far east as Slovenia.

St Patrick attempted to organise the Irish church into a diocesan structure but as things turned out a monastic ecclesial structure quickly became dominant due mainly to the fact that the wild Celtic countries did not have towns, but rather the monasteries became educational, trade and administrative centres for the small kingdoms and the clans which ruled them. In the case of Kildare, for example, St Brigid and her successors as Abbess, ruled the surrounding countryside as the administrative ecclesial power, though naturally the Abbesses worked closely with a bishop who provided the necessary sacraments. As well as celibate monks and nuns many of these monastic villages also included married members with families and in fact some Abbots were hereditary, the title and function being passed from father to son, though the Culdee monastic reform movement from the 9th century onwards tried to impose a more regimented lifestyle on the monasteries.

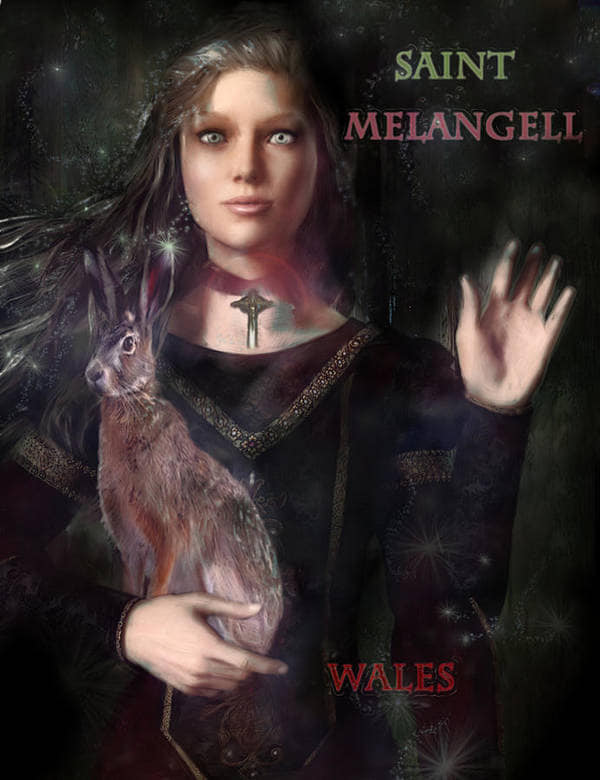

Based as it was on the practices of the Desert Fathers in Egypt, Celtic monasticism was of course heroically ascetical, but so too was the Druidism of earlier times. Both monks and Druids recognised that nothing of lasting value can be acheived without blood, sweat and tears, so wise people and saints were tested and strengthened with various ordeals. One of the most beloved of our Celtic saints is St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, actually an Angle by birth, but also a Celtic monk. He used to wade out into the sea in the evening and remain there, mortifying the flesh, singing psalms thoughout the night, but when he returned to dry land the sea otters would gather around to warm him with their body heat. Many are the tales told of Celtic saints and their animal allies such as St Brigid with her cow, St Melangell of Wales with her hare, St Kevin with his blackbird, St Gobnait with her bees and many saints with wolves and deer. Actually, St Patrick was said to have shape-shifted into the form of a deer on one occasion to escape a dangerous situation, and there is definitely something very close to shamanism in the kinship between Celtic saints and their animal companions.

St Patrick attempted to organise the Irish church into a diocesan structure but as things turned out a monastic ecclesial structure quickly became dominant due mainly to the fact that the wild Celtic countries did not have towns, but rather the monasteries became educational, trade and administrative centres for the small kingdoms and the clans which ruled them. In the case of Kildare, for example, St Brigid and her successors as Abbess, ruled the surrounding countryside as the administrative ecclesial power, though naturally the Abbesses worked closely with a bishop who provided the necessary sacraments. As well as celibate monks and nuns many of these monastic villages also included married members with families and in fact some Abbots were hereditary, the title and function being passed from father to son, though the Culdee monastic reform movement from the 9th century onwards tried to impose a more regimented lifestyle on the monasteries.

Based as it was on the practices of the Desert Fathers in Egypt, Celtic monasticism was of course heroically ascetical, but so too was the Druidism of earlier times. Both monks and Druids recognised that nothing of lasting value can be acheived without blood, sweat and tears, so wise people and saints were tested and strengthened with various ordeals. One of the most beloved of our Celtic saints is St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, actually an Angle by birth, but also a Celtic monk. He used to wade out into the sea in the evening and remain there, mortifying the flesh, singing psalms thoughout the night, but when he returned to dry land the sea otters would gather around to warm him with their body heat. Many are the tales told of Celtic saints and their animal allies such as St Brigid with her cow, St Melangell of Wales with her hare, St Kevin with his blackbird, St Gobnait with her bees and many saints with wolves and deer. Actually, St Patrick was said to have shape-shifted into the form of a deer on one occasion to escape a dangerous situation, and there is definitely something very close to shamanism in the kinship between Celtic saints and their animal companions.

In the early centuries there were some minor differances between the customs of the churches in Celtic countries and those of most of the rest of Europe, such as the date of Easter, which Celts calculated according to the Egyptian Coptic tradition and the style of the clerical tonsure - the Irish and Scottish monks kept the Druidic tonsure, shaving the head at the front from ear to ear but leaving the hair to grow long at the back. There were also some liturgical variations of the Roman Rite, that in recent years have been given new life by ourselves and some other small Celtic churches, yet I think it fair to say that the main distinguishing feature of Celtic Christianity was not these little variations but rather an underlying theology which we might express in these words from Genesis, “And God saw all that he had made and behold it was very good”. We believe, as our ancestors did before us, in Original Blessing and not in Original Sin, and whilst acknowledging that sometimes nature is indeed “red in tooth and claw” our theology is and always has been “panentheistic”, that is the Divine is not confined to the material universe but rather the universe, ourselves included, is infused with the presence of God. We emphasise the Divine immanence in humanity and the natural world, as well as the Divine as transcendent mystery. St Paul also reminded us of the panentheistic vision when he was speaking to the Greek Philosophers, and said, as it is written in the Acts of the Apostles, “For in Him we live and move and have our being.’ As some of your own poets have said, ‘We are His offspring.’” And again in his epistle to the Colossians St Paul wrote,

“There is only Christ. He is everything and he is in everything.” (Colossians 3:11) To the Celtic hermit God was ever present, both in his heart and in the world around him.

To give you a feel for this spirituality of Divine immanance I will read you a poem entitled the “A Hermit’s Desire, attributed to St Kevin of Glendalough, who lived in Ireland in the 6th century.

“I wish, ancient and eternal King, to live in a hidden hut in the wilderness.

A narrow blue stream beside it, and a clear pool for washing away my sins by the grace of the Holy Spirit.

A beautiful wood all around, where birds of every kind of voice can grow up and find shelter.

Facing southwards to catch the sun, with fertile soil around it suitable for every kind of plant.

And virtuous young men to join me, humble and eager to serve you.

Twelve young men – three fours, four threes, two sixes, six pairs – willing to do every kind of work.

A lovely church, with a white linen cloth over the altar, a home for you from Heaven.

A Bible surrounded by four candles, one for each of the gospels.

A special hut in which to gather for meals, talking cheerfully as we eat, without sarcasm, without boasting, without any evil words.

Hens laying eggs for us to eat, leeks growing near the stream, salmon and trout to catch, and bees providing honey.

Enough food and clothing given by you, and enough time to sit and pray to you.”

“There is only Christ. He is everything and he is in everything.” (Colossians 3:11) To the Celtic hermit God was ever present, both in his heart and in the world around him.

To give you a feel for this spirituality of Divine immanance I will read you a poem entitled the “A Hermit’s Desire, attributed to St Kevin of Glendalough, who lived in Ireland in the 6th century.

“I wish, ancient and eternal King, to live in a hidden hut in the wilderness.

A narrow blue stream beside it, and a clear pool for washing away my sins by the grace of the Holy Spirit.

A beautiful wood all around, where birds of every kind of voice can grow up and find shelter.

Facing southwards to catch the sun, with fertile soil around it suitable for every kind of plant.

And virtuous young men to join me, humble and eager to serve you.

Twelve young men – three fours, four threes, two sixes, six pairs – willing to do every kind of work.

A lovely church, with a white linen cloth over the altar, a home for you from Heaven.

A Bible surrounded by four candles, one for each of the gospels.

A special hut in which to gather for meals, talking cheerfully as we eat, without sarcasm, without boasting, without any evil words.

Hens laying eggs for us to eat, leeks growing near the stream, salmon and trout to catch, and bees providing honey.

Enough food and clothing given by you, and enough time to sit and pray to you.”

At this point you may be asking yourself, what was the purpose of this lifestyle. What did they hope to acheive? I think it is true to say that like monks and nuns everywhere the Celtic hermit monastics were “Seeking God”… The Benedictines sought God in the cloister, in reading the bible and praying in church, whereas the Celtic monk sought God primarily in the wilderness, in the woods and wild untamed places where the untamed man within could come to the surface and gradually be healed of the infirmity of sin. It was and is fundamentally a process of self-realisation and reintegration into the Godhead, very similar to the hesychastic path towards theosis still practiced today by Orthodox monastics. As St. Columbanus said, “Therefore let us concern ourselves with heavenly things, not human ones, and like pilgrims always sigh for our homeland, long for our homeland.” That homeland is Divine Union, God-realisation or Enlightenment.

The Celtic eremitical model of monasticism continued through the first millenium and the more urban Benedictine model, the backbone of the Church in England, never took root in the wild Celtic lands of the west, yet the 12th century Cistercian reform, being more agricultural than cultural, and with a particular emphasis on devotion to the Immaculate Mother of God, really appealed to the Celts and gradually supplanted the older form of Celtic monasticism.

I have spoken a great deal about Celtic monasticism, without which a distinctive Celtic Christianity simply would not exist, but there is also something to be said about folk religion - those prayers, poems, stories and rituals handed down in families and communities, devotions to various Celtic saints and pilgrimages to sacred wells, stones and trees associated with them, which have survived right through the centuries to the present day. When the monasteries were suppressed throughout the British Isles in the 16th century, folk Catholicism in Ireland and the Western Isles of Scotland and the Bardic tradition in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany preserved many valuble oral traditions and practices that have contributed to a revival of the Celtic tradition in the 20th century. For example, the Celtic blessings with which you may be familiar probably either come from, or are inspired by, the collection of ancient prayers, poems and charms collected into a book called the Carmina Gadelica by Alexander Carmichael in Scotland and published in 1900.

Various Celtic churches have been founded in the 20th century, some in America which are about as authentic and true to tradition as plastic leprechauns and green beer for St Patrick’s Day, though to be fair, one of the greatest scholars of early Celtic liturgies was also an American and a Celtic Orthodox bishop. The roots of our own church, the Holy Celtic Church International, are in Liberal Catholicism, a branch of Old Catholicism, founded in England in 1917 as well as the Holy Celtic Church of Brittany founded in 1957. We hold more than forty distinct lines of Apostolic Succession from Roman Catholicism, Old Catholicism, Anglicanism and nearly all the branches of Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy. Apostolic Succession and the traditional theory and practice of the sacrament of Holy Orders is vital to the maintenance of our tradition. It is our most prized possession, for as St Ignatius of Antioch wrote back in the 2nd century, “Wherever the bishop is, there is the people of God; just as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church.” And as Tertullian wrote in the 3rd century, “Let them produce the original records of their churches; let them unfold the roll of their bishops, running down in due succession from the beginning in such a manner that the bishop shall be able to show for his ordainer and predecessor some one of the apostles or of apostolic men.” For us, the Apostolic succession is a channel of spiritual power, yet we also recognise that God’s grace cannot be confined to traditional channels. His Holy Spirit certainly moves in groups of Christians outside the Apostolic Succession and indeed the same Spirit is also discernable in members of other religions and none.

The Celtic eremitical model of monasticism continued through the first millenium and the more urban Benedictine model, the backbone of the Church in England, never took root in the wild Celtic lands of the west, yet the 12th century Cistercian reform, being more agricultural than cultural, and with a particular emphasis on devotion to the Immaculate Mother of God, really appealed to the Celts and gradually supplanted the older form of Celtic monasticism.

I have spoken a great deal about Celtic monasticism, without which a distinctive Celtic Christianity simply would not exist, but there is also something to be said about folk religion - those prayers, poems, stories and rituals handed down in families and communities, devotions to various Celtic saints and pilgrimages to sacred wells, stones and trees associated with them, which have survived right through the centuries to the present day. When the monasteries were suppressed throughout the British Isles in the 16th century, folk Catholicism in Ireland and the Western Isles of Scotland and the Bardic tradition in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany preserved many valuble oral traditions and practices that have contributed to a revival of the Celtic tradition in the 20th century. For example, the Celtic blessings with which you may be familiar probably either come from, or are inspired by, the collection of ancient prayers, poems and charms collected into a book called the Carmina Gadelica by Alexander Carmichael in Scotland and published in 1900.

Various Celtic churches have been founded in the 20th century, some in America which are about as authentic and true to tradition as plastic leprechauns and green beer for St Patrick’s Day, though to be fair, one of the greatest scholars of early Celtic liturgies was also an American and a Celtic Orthodox bishop. The roots of our own church, the Holy Celtic Church International, are in Liberal Catholicism, a branch of Old Catholicism, founded in England in 1917 as well as the Holy Celtic Church of Brittany founded in 1957. We hold more than forty distinct lines of Apostolic Succession from Roman Catholicism, Old Catholicism, Anglicanism and nearly all the branches of Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy. Apostolic Succession and the traditional theory and practice of the sacrament of Holy Orders is vital to the maintenance of our tradition. It is our most prized possession, for as St Ignatius of Antioch wrote back in the 2nd century, “Wherever the bishop is, there is the people of God; just as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church.” And as Tertullian wrote in the 3rd century, “Let them produce the original records of their churches; let them unfold the roll of their bishops, running down in due succession from the beginning in such a manner that the bishop shall be able to show for his ordainer and predecessor some one of the apostles or of apostolic men.” For us, the Apostolic succession is a channel of spiritual power, yet we also recognise that God’s grace cannot be confined to traditional channels. His Holy Spirit certainly moves in groups of Christians outside the Apostolic Succession and indeed the same Spirit is also discernable in members of other religions and none.

Marit also asked me to say a few words about Christmas and give you a few Christmas preaching ideas, but sadly I must confess right away that preaching is not my forte, so I asked around my clergy friends and one, an Anglican priest who is also a member of our community, told me that for many years for the Christmas morning Parish Mass he would ask in advance for each child to bring one of the Christmas gifts they had received and at the time of the sermon he would look at all the gifts and compose a homily there and then referring to each of them. This could sometimes yield surprising insigts and it was a bit of fun that the families appreciated. Perhaps it’s something you may like to try?

However, in our church we are mainly solitaries or minister only to small groups of family and friends so we rarely have any occasion for formal preaching. Teaching, yes certainly, but preaching very rarely, as we prefer to let the words of the liturgy speak for themselves and of course we also regularly celebrate the Liturgy of the Hours, Lectio Divina and Meditation, so, hopefully, we do “listen to the words of the Master”, as St Benedict recommends. We also appreciate these words of St Francis "Preach the Gospel at all times. Use words if necessary.” Therefore, all that really needs to be said is that Christmas reminds us that God is “Emmanuel” - “God with us” and more than that, in the Celtic tradition we would say God with us, God within us, above us, below us and all around us.

For me the essence of Christmas is summed up in the words of this well known hymn, “

O holy Child of Bethlehem!

Descend to us, we pray;

Cast out our sin, and enter in,

Be born in us to-day.

We hear the Christmas angels

The great glad tidings tell;

Oh, come to us, abide with us,

Our Lord Emmanuel!

I would like now, if I may, to close with a blessing. Let us pray: “As the sun rises over woods and sets upon the same, Lord bring your Yule blessings of good cheer. As the fire rises on the hearth, Lord bless us all with the warmth of your love, As the gift is given in the quiet of darkness, Lord bless us all and all we know with the surprise of your nearness. Amen. “

(Blessing by the Revd Tess Ward)

However, in our church we are mainly solitaries or minister only to small groups of family and friends so we rarely have any occasion for formal preaching. Teaching, yes certainly, but preaching very rarely, as we prefer to let the words of the liturgy speak for themselves and of course we also regularly celebrate the Liturgy of the Hours, Lectio Divina and Meditation, so, hopefully, we do “listen to the words of the Master”, as St Benedict recommends. We also appreciate these words of St Francis "Preach the Gospel at all times. Use words if necessary.” Therefore, all that really needs to be said is that Christmas reminds us that God is “Emmanuel” - “God with us” and more than that, in the Celtic tradition we would say God with us, God within us, above us, below us and all around us.

For me the essence of Christmas is summed up in the words of this well known hymn, “

O holy Child of Bethlehem!

Descend to us, we pray;

Cast out our sin, and enter in,

Be born in us to-day.

We hear the Christmas angels

The great glad tidings tell;

Oh, come to us, abide with us,

Our Lord Emmanuel!

I would like now, if I may, to close with a blessing. Let us pray: “As the sun rises over woods and sets upon the same, Lord bring your Yule blessings of good cheer. As the fire rises on the hearth, Lord bless us all with the warmth of your love, As the gift is given in the quiet of darkness, Lord bless us all and all we know with the surprise of your nearness. Amen. “

(Blessing by the Revd Tess Ward)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed